Chapters

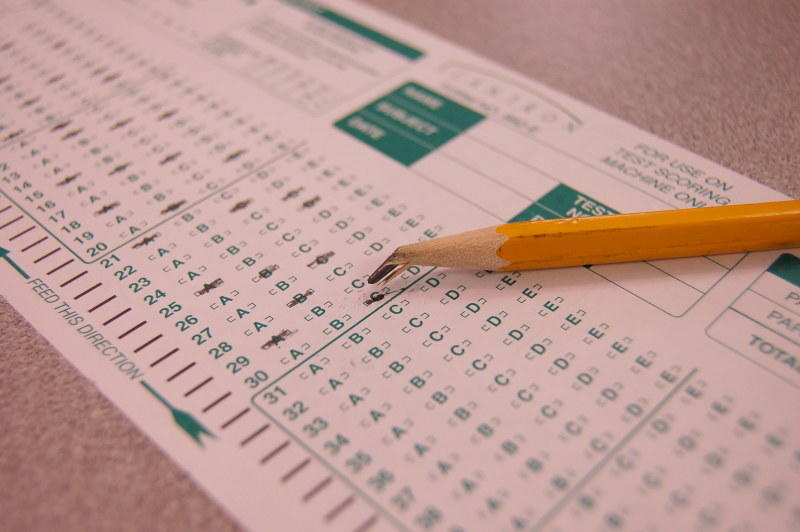

For some reasons, students feel equal parts of relief and elation when told that their exam will be, at least in part, multiple choice. None of those maddening essay questions, wherein your penmanship and syntax use could bring your grade down. Just a straightforward "Is the answer this, that or the other?"... Yippee!

At a glance, these tests may seem like the easier, less stressful option. You don’t need to write an inordinate amount of text, discuss or defend your points of view. Yet they can also be some of the trickiest tests to pass.

Sometimes the questions are ambiguous. For instance, if the question reads "When was the Industrial Revolution?", the answers might list the dates for both the first and the fourth revolutions - with no selection for multiple dates available. So which answer will be deemed correct?

Conversely, students have come to recognise that selections such as "Both 'B' and 'C' are correct" are often the correct answer. So test authors have started randomly including them throughout their exams even though it is not the right answer. Why would anyone want to trick students to test their academic competence? Especially when you know that

- multiple-choice exams began a quick and easy way to qualify soldiers for battle

- surveys, polls and even television game shows feature the multiple-choice format

- often, multiple-choice exams are not intellectually challenging

- intuitive test takers can simply guess their answers with an equal probability of being right

- you can increase your odds for a good result by following a few simple strategies

With all that now said, why would anyone believe that multiple choice exams accurately reflect students' mastery over a subject? Superprof wants to explore the shady origins of multiple choice testing. And then, we'll tell you how you too could score higher on such exams.

The Origins of Multiple Choice Testing

It's 1917 and the world is in chaos. Every European country is engaged in the bloody business of war. Asian countries, not to be outdone, were fighting battles over their own issues and interests. When the Germans torpedoed the Lusitania with 12 Americans on board, the US abandoned its policy of non-intervention and joined in the fighting.

There was just one problem: the US Army needed a quick way to test the intelligence of potential recruits. Dr Robert Yerkes felt that the written and oral exams were too time-consuming and cumbersome. Such tests were the standard of the day for military enlistment, administered on a broad scale to every male of fighting age.

Dr Yerkes had an ulterior motive for promoting multiple-choice tests. He was the head of the American Psychological Association at that time. He wanted psychology to be accepted as legitimate science.

The Department of War administered his test to nearly 2 million recruits. They ultimately found no value in the results. The tests gave no indication of how these men would function under fire or how well they could follow orders.

Undaunted, Dr Yerkes pitched his testing format to educational testing bodies, Pearson Education among them. You might know that name; it is the organisation that develops and administers so many of our academic exams today. He left off the part about his test being deemed ineffective.

After the war, there was a growing interest in psychology. That fascination paved the way for Dr Yerkes' tests to fairly waltz into academic programmes with nary a complaint or objection raised. By 1926, multiple choice exams were the standard for college admissions exams. By 1930, they and true/false questions were used in schools across the country and at all levels of education.

From there, they travelled around the world. Today, they feature in virtually every academic programme and centre of learning. Unfortunately, besides not being a true reflection of a person's ability to reason, there is one more insidious bit of nastiness in the history of multiple choice exams.

At that time, in the US, the social class system was alive and well. The intent to preserve that status quo meshed well with the growing desire to measure students' progress. Multiple choice exams served both purposes.

Quick to administer, easy to interpret and pervasive in all aspects of education, these tests results were often used to elevate the 'better' students. They also reinforced the idea that 'lesser' students were incapable of outperforming their betters. To this day, we interpret academic performance as an indicator of status in society, even if that society is contained in the schoolyard. And even if your child isn't well settled in school and performs poorly.

Multiple Choice in Popular Culture

Have you ever watched 'Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?'? The fact is, we've been making selections from multiple choice questions practically all of our lives. When your mum asked if you want to wear your red jumper today, your blue one... or would the green one be better, you were making a choice. When you're at McDonald's and they ask if you want Sprite, Coke or a diet drink... guess what? That too is multiple choice.

Some students earn extra income from taking marketing surveys - either online or in person. Often, the questions posed are multiple choice. If you visit a doctor's surgery, you may be asked to take a short survey at the end of your visit. Think about how those surveys are formulated: they ask a question and give you a range of answers to choose from.

For example: "How satisfied are you with your visit today?" or "Did the doctor answer all of your questions?". You may see a ranking, with 1 indicating you're not satisfied and the doctor did not do a good job. On the other end of the spectrum, maybe a 5: the doctor did a great job and you're very satisfied.

Multiple choice is everywhere and, once you see it, it's hard to un-see exactly how pervasive it really is. It's a popular game show format - once that incorporates this question format's little sister, the true/false question (in Millionaire, it's the 50/50 option). Millionaire is probably the best-known example of a multiple choice game show. However, it was definitely not the first on the market.

American game shows like The Price is Right, Funny You Should Ask and Press Your Luck enjoyed fairly long runs. The Price is Right (debut: 1972) is running still today while others are re-running in syndication. However, unlike games such as The Weakest Link, they do not require players to have any specific knowledge, only an ability to choose well.

The multiple choice format is, in turn, revered or reviled. Often, it's not even noticed. But like it or not, these games aren't going anywhere, and neither are multiple choice exams. Even homeschooled learners take them sometimes.

The Pros and Cons of Multiple Choice Exams

The pros of this type of exam are obvious: they're quick and (relatively) easy to sit, they don't require you to lay out any arguments or defend your ideas. From the administrators' side: they're easy to score and, with the Department for Education making no requirements for in-depth assessments, provide a quick way for teachers to post the necessary grades.

Multiple choice exams are like getting dinner from a fast-food drive-through window. Such a meal can be quickly obtained and will quell your hunger with little effort involved but, in the end, it's not the best food for you to eat. Nor does it challenge your culinary skills or give you the satisfaction of having accomplished anything remarkable. To be sure, a fast food meal just hits the spot sometimes but, if you ate a steady diet of it...

Most university students take their education seriously. In that sense, multiple choice exams do them a disservice because they do little to show learners where the gaps in their knowledge are. Multiple choice is less an exposé of students' knowledge stores than it is an exercise in gambling.

Let's say you're in your last year of undergraduate study for your Art History degree. You may sit in your usual seat and I'll take the one across the aisle. I do not have the benefit of three years of study in your field but I am just as capable of guessing a correct answer simply by noting patterns.

For instance, the test probably wouldn't have four 'A' answers in a row, nor is the answer key likely to be ABCD or a similar orderly pattern. You can see how easy it could be to score decently just by following the laws of probability, right? Successful gamblers do it all the time!

In this article's introduction, we mentioned ambiguously-phrased questions. Sticking with Art History, let's say that one multiple choice test question reads: Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec is most famous for:

- a: painting colourful scenes of Paris theatre life

- b: being a post-impressionist painter

- c: his short stature

- d: his bawdy lifestyle

All of these answers are facts about this famous painter. Some people know him best because of his raging alcoholism and carousing with prostitutes (answer D) while others may believe that his short stature made him most famous. Which answer is does the test's author indicate as the correct one?

Subjective, ambiguous questions such as these are only a part of the problem. Another is deliberately tricking test takers with answers that look nearly right or feel right. But through wordplay or deliberate misdirection, they lead the student to select the wrong answer.

We gave an example of deliberate misdirection in this article's intro (both B and C are correct). The wordplay in question may be anything from using an antonym instead of a synonym or using a homonym. For instance: 'The brake under his foot left him permanently injured' versus 'He was permanently injured by the break on the sole of his foot'.

Flying through the test, a student might mistakenly check the first answer as correct even though it uses the wrong spelling of 'break'. To help avoid some of these grading pitfalls, we leave you with a few tips for scoring better on this type of exam. Especially if you're an autonomous learner trained in critical thinking.

Getting Closer to Success on Multiple Choice Exams

Before we start, some points to consider. One, a well-drafted test depends greatly on the examiner’s ability at making a clear distinction between choices. Secondly, students can fall into the trap of skimming through the options quickly. They might mark off the first answer that seems right without ‘checking the fine print’.

Finally, multiple-choice tests have the uncanny ability to leave students feeling rather insecure after the test. ‘Have I answered correctly?’ ‘Is there any chance I have overlooked the right answer?’. These are typical questions students often ask themselves after a multiple choice test.

Essay questions may be more difficult and time-consuming for both the instructor and the student. However, if you know the subject matter and you have made it a point to answer the exact question posed to you, chances are good that your grades will reflect your effort. Not so with multiple choice tests. Still, scoring well on such exams is not an insurmountable obstacle, no matter how hard they seem. Follow these tips and don’t be a victim of confusion and insecurity:

Read the questions carefully. Some questions can be trickily worded, meant to trap, as it were, careless minds or those who whiz through questions with a false sense of confidence. Watch out for ‘double negative’ questions, such as “Which of these statements cannot be classified as untrue” – which is, of course, a convoluted way of saying, “Which of these statements is true?”.

Read ALL the options – don’t choose an answer until you have done so. When you encounter what you think is the right answer, you may select it haphazardly. Reading all the answers encourages you to question whether your initial selection was right. Very often, it will make you change your mind altogether and realise that a word or two in your initial answer skews the meaning of a statement and makes it incorrect.

Don’t dwell too long on difficult answers: Even in the case of multiple choice tests, you need to allocate a specific amount of time to each question. Say the test lasts for an hour and five minutes there are 30 questions. You should try to spend more than two minutes on each question and allocate five minutes for revision. If you are having difficulty with a particular question, leave it and come back to it later. Most of the easier questions will take much less time, so you will find that you probably have a few spare minutes to use on questions you have gotten stuck on previously. Leaving a question to later may also allow you to approach the question from a new perspective.

Revise your work: Always allocate time for revision. Most students find glaring mistakes and then cannot believe they didn’t spot the first time around at the revision stage. Use your instinct and spend the most time on the questions you have found the trickiest; if you feel that something about an answer is not quite right, chances are, you’re right.

These tips apply whether you learn in a home-school or a traditional setting. We hope that you have found these tips useful. If you would like to share them, please do. Also, if you have some things that you have found work for you, please share them with us via the comments section below.